The Complicity of NGOs in Creating Fake News on Palm Oil

New York Times (2018) Palm Oil Was Supposed to Help Save the Planet. Instead It Unleashed a Catastrophe. A decade ago, the U.S. mandated the use of vegetable oil in biofuels, leading to industrial-scale deforestation — and a huge spike in carbon emissions.

CNN (2019) Kalimantan, Indonesia — Deep within the jungles of Indonesian Borneo, illegal fires rage, creating apocalyptic red skies and smoke that has spread as far as Malaysia and Singapore.

People are choking. Animals are dying. This is no ordinary fire. It was lit for you.

CNN (2019) Kalimantan, Indonesia — Deep within the jungles of Indonesian Borneo, illegal fires rage, creating apocalyptic red skies and smoke that has spread as far as Malaysia and Singapore.

People are choking. Animals are dying. This is no ordinary fire. It was lit for you.

When palm oil is featured in media like the New York Times and CNN as bad for people and planet, it’s a hard fight for the palm oil industry.

The industry was invincible in the early years of its boom. It didn’t matter what accusations were leveled against it, there were willing buyers lined up across the world.

The situation remains to this day where boycotts and bans of palm oil by a handful of Western consumers to “save rainforests from palm oil” have been silenced by the billions of consumers in India, China and even in Western countries who demand an affordable vegetable oil.

However, the reputational damage from a ban from the lucrative market of EU biofuels has seen strong reactions from the main palm oil producing countries of Indonesia and Malaysia.

The reason for the strong reactions is that both countries have been working towards the sustainability of the palm oil sector as part of their national commitments to develop sustainably. The EU ban was seen as a slight of the national certifications in the Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil (MSPO) and Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO) which represent the countries efforts towards sustainable palm oil production.

Their efforts could use the support of conservation-minded markets like the EU but some MEPs unfortunately, hold an extremely negative view of palm oil.

The industry was invincible in the early years of its boom. It didn’t matter what accusations were leveled against it, there were willing buyers lined up across the world.

The situation remains to this day where boycotts and bans of palm oil by a handful of Western consumers to “save rainforests from palm oil” have been silenced by the billions of consumers in India, China and even in Western countries who demand an affordable vegetable oil.

However, the reputational damage from a ban from the lucrative market of EU biofuels has seen strong reactions from the main palm oil producing countries of Indonesia and Malaysia.

The reason for the strong reactions is that both countries have been working towards the sustainability of the palm oil sector as part of their national commitments to develop sustainably. The EU ban was seen as a slight of the national certifications in the Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil (MSPO) and Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO) which represent the countries efforts towards sustainable palm oil production.

Their efforts could use the support of conservation-minded markets like the EU but some MEPs unfortunately, hold an extremely negative view of palm oil.

Satellite Mapping, Remote Sensing and the Burden of Proof

The negative sentiment against palm oil requires that palm oil producing countries back up their claims of sustainability with a burden of proof through new technologies.

This is absolutely essential as well meaning groups like Rainforest Alliance, which certifies sustainable palm oil, uses old data from World Resources Institute to accuse the global palm oil industry of:

“being the second biggest driver of global tree cover loss and a top driver of biodiversity loss. Additionally, its rapid expansion has fueled greenhouse gas emissions.”

This is nowhere near the truth in 2022.

Jean-Marc Roda from CIRAD had published a report in 2019 “The geopolitics of palm oil and deforestation” that showed forest loss in Indonesia and Malaysia was being wrongly blamed on palm oil.

His findings were supported by a 2022 report from Satelligence which has been monitoring the dynamics of deforestation of several commodities in Indonesia via satellite over the last 20 years

So how did palm oil get such a bad rap for deforestation? Older remote sensing technology created the problem by presenting false information as factual.

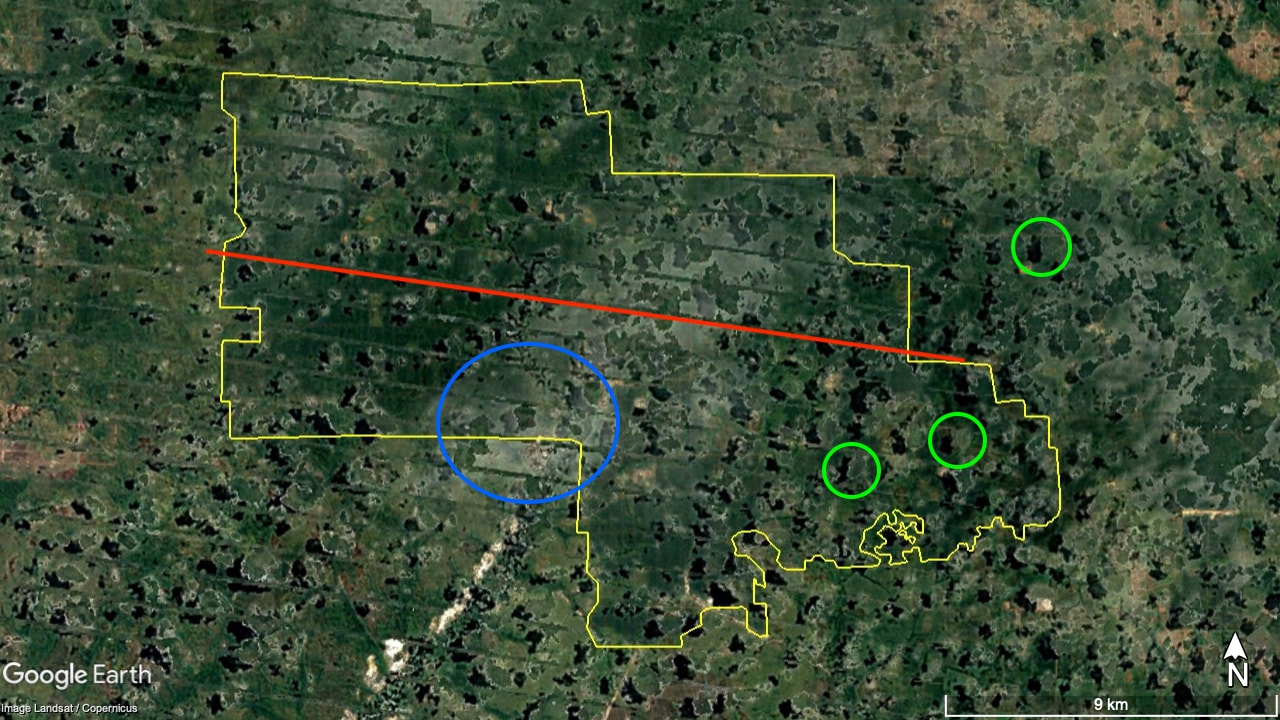

According to Bart van Assen, who coined the term “Pretty Earth Fallacy,” Google Earth remote sensing as used by people like Roberto Cazzolla Gatti to claim that “Certified “sustainable” palm oil took the place of endangered Bornean and Sumatran large mammals habitat and tropical forests in the last 30 years” are guilty of creating fallacies.

“Satellites are in some ways like cameras but in other ways very different: they record light, but in a very different way. They also record light invisible to the human eye, in particular in the infrared (IR) and near infrared (NIR) spectrum.

Hence, the data from satellites is often converted to be visualized and is always done so with a certain bias to emphasize certain aspects. E.g. the NIR is converted to green to display biomass,

It is also worth noting that until recently, the resolution of satellite imagery was very course at 60x60 m. This simply didn’t allow for an accurate identification of intact tropical forest.”

Yet another point of importance is the abundance of clouds in the wet tropics, which are cut away (while their shadows remain) in all pretty earth imagery.

All of the above is ignored by journalists and dishonest scientists: they present google historical imagery as actual photographs of earth, even refer to it as satellite images. They then interpret dark green (including cloud shadows) as intact rainforest. A great example is Aidenvironment “interpreting” agricultural land as intact tropical forest:

When challenged about their inaccurate information, Aidenvironment employees argued that the results justified the means, that their false information would ensure that deforestation would stop.”

Aidenvironment is no stranger to controversy in its mapping work. A rich contract with Genting Plantations where its advice to the company on “go no-go” areas ended up being severely criticized by an Indonesian group.

That was a small case according to Bart van Assen who brought up the sensational case of Greenpeace vs PT Smart. Based on map work supplied by Aidenvironment, Greenpeace accused PT Smart of deforestation which led to the company being cut out of supply agreements with palm oil buyers like Unilever.

PT Smart reacted with an independent verification of Greenpeace’s accusations by appointing two Certification Bodies, Control Union Certifications (CUC) and BSI Group (BSI), and experts from Faculty of Forestry, Bogor Agriculture Institute (IPB) to review the accusations.

The reviews addressed Greenpeace’s reports including “Burning Up Borneo,” “RSPO Greenwash”, “Caught Red Handed”, “New Evidence: Sinar Mas – Rainforest and Peatland Destruction”, and “Sinar Mas Continues Rainforest Destruction”

The Independent Verification Report (IVEX) which resulted was used successfully to challenge Greenpeace’s accusations.

In the hope of preventing future gaffs by NGOs looking to make a name for themselves by attacking palm oil production in Indonesia, Bart published a paper in 2021 to debunk the myths of palm oil and deforestation in Indonesia.

“In a nutshell, our paper notes how of the land planted with oil palms starting 1992 half was already abandoned lands and agricultural mosaics in 1984 (about a decade earlier) while the other half was (heavily) degraded forest then. Hence, no (near) intact forests were converted for the estates we sampled! I believe this to be the case for 90% of the oil palm cultivation in Indonesia: oil palm cultivation follows after deforestation rather than causes it.”

As the European Union seeks closer ties with Southeast Asian nations with a full summit this December, the top priority for palm oil producing countries should be to remove the controversial matter of palm oil and its purported impact on forests. Balancing the geopolitical securities will not be an easy task for the EU which is facing protests against its deforestation policy from other nations.

With the pending EU legislation to stop imported deforestation through Corporate Due Diligence, the availability of precise satellite mapping will be essential for palm oil producers to verify that their palm oil, did not cause deforestation.

Published September, 2022. CSPO Watch

The negative sentiment against palm oil requires that palm oil producing countries back up their claims of sustainability with a burden of proof through new technologies.

This is absolutely essential as well meaning groups like Rainforest Alliance, which certifies sustainable palm oil, uses old data from World Resources Institute to accuse the global palm oil industry of:

“being the second biggest driver of global tree cover loss and a top driver of biodiversity loss. Additionally, its rapid expansion has fueled greenhouse gas emissions.”

This is nowhere near the truth in 2022.

Jean-Marc Roda from CIRAD had published a report in 2019 “The geopolitics of palm oil and deforestation” that showed forest loss in Indonesia and Malaysia was being wrongly blamed on palm oil.

His findings were supported by a 2022 report from Satelligence which has been monitoring the dynamics of deforestation of several commodities in Indonesia via satellite over the last 20 years

So how did palm oil get such a bad rap for deforestation? Older remote sensing technology created the problem by presenting false information as factual.

According to Bart van Assen, who coined the term “Pretty Earth Fallacy,” Google Earth remote sensing as used by people like Roberto Cazzolla Gatti to claim that “Certified “sustainable” palm oil took the place of endangered Bornean and Sumatran large mammals habitat and tropical forests in the last 30 years” are guilty of creating fallacies.

“Satellites are in some ways like cameras but in other ways very different: they record light, but in a very different way. They also record light invisible to the human eye, in particular in the infrared (IR) and near infrared (NIR) spectrum.

Hence, the data from satellites is often converted to be visualized and is always done so with a certain bias to emphasize certain aspects. E.g. the NIR is converted to green to display biomass,

It is also worth noting that until recently, the resolution of satellite imagery was very course at 60x60 m. This simply didn’t allow for an accurate identification of intact tropical forest.”

Yet another point of importance is the abundance of clouds in the wet tropics, which are cut away (while their shadows remain) in all pretty earth imagery.

All of the above is ignored by journalists and dishonest scientists: they present google historical imagery as actual photographs of earth, even refer to it as satellite images. They then interpret dark green (including cloud shadows) as intact rainforest. A great example is Aidenvironment “interpreting” agricultural land as intact tropical forest:

When challenged about their inaccurate information, Aidenvironment employees argued that the results justified the means, that their false information would ensure that deforestation would stop.”

Aidenvironment is no stranger to controversy in its mapping work. A rich contract with Genting Plantations where its advice to the company on “go no-go” areas ended up being severely criticized by an Indonesian group.

That was a small case according to Bart van Assen who brought up the sensational case of Greenpeace vs PT Smart. Based on map work supplied by Aidenvironment, Greenpeace accused PT Smart of deforestation which led to the company being cut out of supply agreements with palm oil buyers like Unilever.

PT Smart reacted with an independent verification of Greenpeace’s accusations by appointing two Certification Bodies, Control Union Certifications (CUC) and BSI Group (BSI), and experts from Faculty of Forestry, Bogor Agriculture Institute (IPB) to review the accusations.

The reviews addressed Greenpeace’s reports including “Burning Up Borneo,” “RSPO Greenwash”, “Caught Red Handed”, “New Evidence: Sinar Mas – Rainforest and Peatland Destruction”, and “Sinar Mas Continues Rainforest Destruction”

The Independent Verification Report (IVEX) which resulted was used successfully to challenge Greenpeace’s accusations.

In the hope of preventing future gaffs by NGOs looking to make a name for themselves by attacking palm oil production in Indonesia, Bart published a paper in 2021 to debunk the myths of palm oil and deforestation in Indonesia.

“In a nutshell, our paper notes how of the land planted with oil palms starting 1992 half was already abandoned lands and agricultural mosaics in 1984 (about a decade earlier) while the other half was (heavily) degraded forest then. Hence, no (near) intact forests were converted for the estates we sampled! I believe this to be the case for 90% of the oil palm cultivation in Indonesia: oil palm cultivation follows after deforestation rather than causes it.”

As the European Union seeks closer ties with Southeast Asian nations with a full summit this December, the top priority for palm oil producing countries should be to remove the controversial matter of palm oil and its purported impact on forests. Balancing the geopolitical securities will not be an easy task for the EU which is facing protests against its deforestation policy from other nations.

With the pending EU legislation to stop imported deforestation through Corporate Due Diligence, the availability of precise satellite mapping will be essential for palm oil producers to verify that their palm oil, did not cause deforestation.

Published September, 2022. CSPO Watch

|

|

|