ISPO. Tracking the Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil scheme at CSPO Watch

The Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil scheme or ISPO is being revamped in 2020 in an attempt for global acceptance of its certificates.

The key change to the ISPO certification scheme is that it has been upgraded from a Ministerial regulation to a Presidential regulation. As reported by Mongabay Indonesia:

“Presidential Regulation No. 44/2020 on Indonesian Sustainable Palm Plantation certification system was revamped in March 2019, by requiring companies or planters or independent smallholders to have Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO) certification by 2025."

The key change to the ISPO certification scheme is that it has been upgraded from a Ministerial regulation to a Presidential regulation. As reported by Mongabay Indonesia:

“Presidential Regulation No. 44/2020 on Indonesian Sustainable Palm Plantation certification system was revamped in March 2019, by requiring companies or planters or independent smallholders to have Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO) certification by 2025."

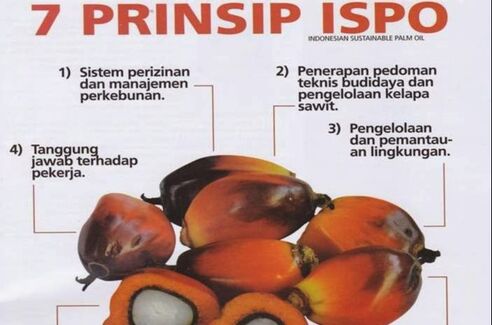

Guiding principles for ISPO, Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil

Guiding principles for ISPO, Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil

The Mongabay report quotes several critics of the ISPO who raised key questions on the sustainability of Indonesian palm oil under the ISPO scheme.

Due to the movement restrictions enforced under Indonesia’s efforts to control the spread of Covid19, the introduction of new standards or guiding principles of the ISPO is delayed. However, insider messages to CSPO Watch indicates that the revision of ISPO standards is an active issue with backroom discussions on-going.

Background on the ISPO

The ISPO was introduced in 2013 as an Indonesian effort to certify its palm oil production. Led by the industry’s biggest association, GAPKI, the ISPO was touted as a diplomatic tool for Indonesia. This report on the ISPO from the Jakarta Post published in 2017 provides some good insights into what has taken place since 2013.

An updated report by Jakarta Post in 2019 indicated that Indonesia is working on strengthening the standards of the ISPO to gain more international recognition. A joint study by the ISPO and the established RSPO from 2016 should have provided some indications of where the ISPO needs to be if it wants global acceptance.

Further indications of where the ISPO needs to be can be seen in the report by Mongabay which quoted several critics of the ISPO scheme including SawitWatch.

Global acceptance notwithstanding, multinational palm oil companies including Wilmar, Golden Agri Resources and Musim Mas have supported the ISPO by complying with the Ministerial regulation for ISPO certification.

Diah Y Suradiredja, the vice chairman of System Empowerment team to strengthen ISPO standards acknowledged the shortfalls of the ISPO when he told Mongabay that this current attempt to revise ISPO standards is a chance to “repair” its shortfalls. Quoting the article:

“This regulatory consideration finds that the legislation governing the certification system is unsuitable for international development and legal needs. It is necessary to change and rearrange the presidential regulation.

This rule has three objectives of ISPO certification, which is, firstly, to ensure and improve the management and development of palm oil plantations according to ISPO principles and criteria. Secondly, increasing the acceptance and competitiveness of palm oil plantation results in national and international markets. Thirdly, increasing the accelerating efforts of reducing greenhouse gas emissions as an effort of Indonesia's climate policy.”

Biodiversity Must Weigh Equally to Poverty Alleviation for ISPO

These are broad targets that must be streamlined and defined with clear principles and defining criteria. Looking at the “acceptance” factor for example, the inclusion of conservation is an absolute must if the ISPO is to find global acceptance. There is no getting around the issue of conservation as most of the accusations of orangutan extinction and deforestation have been based on what the Indonesian palm oil industry has done in recent years.

Current estimates of planted areas for palm oil in Indonesia is <17 million hectares. The projected acreage in its national plan is expected to go beyond 20 million hectares as poorer provinces are developed. Efforts to increase palm oil yield on existing planted areas including the country’s investments in replanting smallholder areas are a laudable step towards increasing revenues from its palm oil industry.

However, Indonesia has to recognize and accept, especially in these days of the Covid19, that buyer countries are wary of any product that is a cause of deforestation which could lead to the next global pandemic. If the ISPO is to achieve global acceptance of its sustainability, it has to show that it is a better option than what scientists are saying about the next potential sources of pandemics including the Amazon or Africa.

The “last remaining frontiers” for Indonesian palm oil expansion in Maluku, Aceh and Papua provinces need clear guidance for successful conservation to prevent what has happened in Kalimantan and Sumatra. Strong guidance on their development based on ISPO standards will undoubtedly add to the credibility of the ISPO standards. In order to achieve this, the ISPO standards must place equal weight on the protection of biodiversity to that of alleviating poverty.

Join us on Twitter @CspoWatch as we track the development of the new standards for the Indonesian Palm Oil Scheme.

Published April, 2020. CSPO Watch

Due to the movement restrictions enforced under Indonesia’s efforts to control the spread of Covid19, the introduction of new standards or guiding principles of the ISPO is delayed. However, insider messages to CSPO Watch indicates that the revision of ISPO standards is an active issue with backroom discussions on-going.

Background on the ISPO

The ISPO was introduced in 2013 as an Indonesian effort to certify its palm oil production. Led by the industry’s biggest association, GAPKI, the ISPO was touted as a diplomatic tool for Indonesia. This report on the ISPO from the Jakarta Post published in 2017 provides some good insights into what has taken place since 2013.

An updated report by Jakarta Post in 2019 indicated that Indonesia is working on strengthening the standards of the ISPO to gain more international recognition. A joint study by the ISPO and the established RSPO from 2016 should have provided some indications of where the ISPO needs to be if it wants global acceptance.

Further indications of where the ISPO needs to be can be seen in the report by Mongabay which quoted several critics of the ISPO scheme including SawitWatch.

Global acceptance notwithstanding, multinational palm oil companies including Wilmar, Golden Agri Resources and Musim Mas have supported the ISPO by complying with the Ministerial regulation for ISPO certification.

Diah Y Suradiredja, the vice chairman of System Empowerment team to strengthen ISPO standards acknowledged the shortfalls of the ISPO when he told Mongabay that this current attempt to revise ISPO standards is a chance to “repair” its shortfalls. Quoting the article:

“This regulatory consideration finds that the legislation governing the certification system is unsuitable for international development and legal needs. It is necessary to change and rearrange the presidential regulation.

This rule has three objectives of ISPO certification, which is, firstly, to ensure and improve the management and development of palm oil plantations according to ISPO principles and criteria. Secondly, increasing the acceptance and competitiveness of palm oil plantation results in national and international markets. Thirdly, increasing the accelerating efforts of reducing greenhouse gas emissions as an effort of Indonesia's climate policy.”

Biodiversity Must Weigh Equally to Poverty Alleviation for ISPO

These are broad targets that must be streamlined and defined with clear principles and defining criteria. Looking at the “acceptance” factor for example, the inclusion of conservation is an absolute must if the ISPO is to find global acceptance. There is no getting around the issue of conservation as most of the accusations of orangutan extinction and deforestation have been based on what the Indonesian palm oil industry has done in recent years.

Current estimates of planted areas for palm oil in Indonesia is <17 million hectares. The projected acreage in its national plan is expected to go beyond 20 million hectares as poorer provinces are developed. Efforts to increase palm oil yield on existing planted areas including the country’s investments in replanting smallholder areas are a laudable step towards increasing revenues from its palm oil industry.

However, Indonesia has to recognize and accept, especially in these days of the Covid19, that buyer countries are wary of any product that is a cause of deforestation which could lead to the next global pandemic. If the ISPO is to achieve global acceptance of its sustainability, it has to show that it is a better option than what scientists are saying about the next potential sources of pandemics including the Amazon or Africa.

The “last remaining frontiers” for Indonesian palm oil expansion in Maluku, Aceh and Papua provinces need clear guidance for successful conservation to prevent what has happened in Kalimantan and Sumatra. Strong guidance on their development based on ISPO standards will undoubtedly add to the credibility of the ISPO standards. In order to achieve this, the ISPO standards must place equal weight on the protection of biodiversity to that of alleviating poverty.

Join us on Twitter @CspoWatch as we track the development of the new standards for the Indonesian Palm Oil Scheme.

Published April, 2020. CSPO Watch