Did Indonesia Just Set A Global Standard for Fighting Climate Change with Forests?

- Indonesia may have just shown the world that pledges to fight climate change must be backed by action.

- Indonesia was a signatory of the Glasgow Deforestation Pledge which went viral on November 2, 2021.

- The Pledge was shared by UK Minister for the International Environment and Climate, and UK Animal Welfare and Forests, Zac Goldsmith who hailed the ‘unprecedented’ deal at Cop26 to save world’s forests as “More than 100 leaders to commit to halting and reversing deforestation and land degradation by 2030.”

|

Lord Goldsmith may have been overzealous in his tweets but Indonesia was clear on where the country stands as far as forests and climate change are concerned.

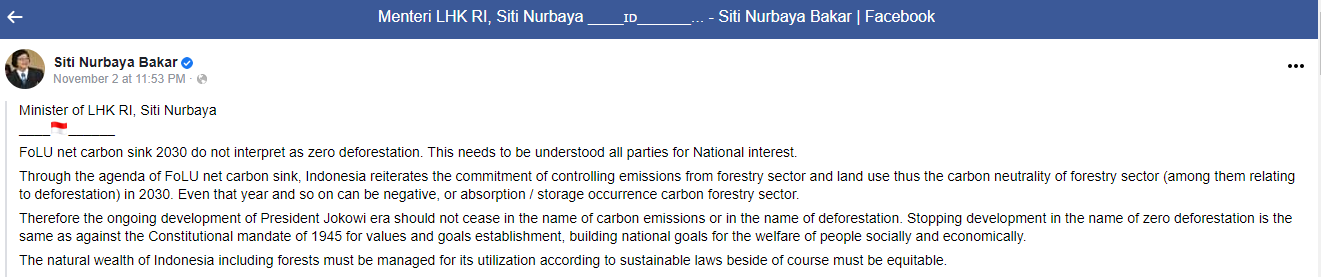

The reaction from Indonesian officials was quick. Indonesia’s Vice Minister for Foreign Affairs Mahendra Sriregar promptly refuted the UK Minister’s statement and said Goldsmith’s tweet was “false and misleading.” To understand Indonesia’s challenge to Lord Goldsmith’s tweet, we have to dial back to November 2, 2021 where Minister for the Environment and Forests, Siti Nurbaya Bakar had outlined on Facebook, what the country’s position on forests was. |

The key words here are that Forests and Land Use (FoLU) which was the title for Lord Goldsmith’s document “World Leaders Summit on Forests and Land Use” was expanded by Lord Goldsmith to mean “halt and reverse forest loss and land degradation by 2030.”

This may sound like pure semantics. After all, what is the difference halt between “and reverse forest loss” as Lord Goldsmith posted or “controlling emissions from the forestry sector and land use” as Minister Bakar posted?

There is a stark difference.

“Halt and reverse forest loss” panders to the popular narrative of “planting trees” to fight climate change. Tree planting exercises may have popular media support but the hard facts and science behind these pop pledges are that they do not fight climate change as claimed.

Take for example:

The independent carbon tracker Carbon Independent sums up the problems well as:

Planting trees will not make a major contribution to tackling the climate crisis. There are many good reasons for planting trees, but sadly, tree planting will not make a significant contribution to the climate crisis.

If the planting of a trillion saplings won’t stop climate change, then surely old forests like those in the lungs of the earth in the Amazonian forests can help buffer its effects?

Maybe not according to the latest report on the Amazon.

As carbon dioxide emissions have surged by 50 percent in 60 years, to nearly 40 billion tonnes worldwide, the Amazon has absorbed a large amount of that pollution—nearly two billion tonnes a year, until recently.

But humans have also spent the past half-century tearing down and burning whole swathes of the Amazon to make way for cattle ranches and farmland.

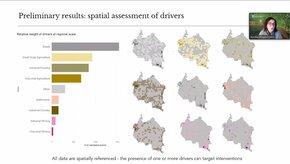

But its not just cattle ranches and farmland that is changing the landscape. As countries develop, infrastructure like roads have been identified by the FAO as the biggest driver of spatial change.

This may sound like pure semantics. After all, what is the difference halt between “and reverse forest loss” as Lord Goldsmith posted or “controlling emissions from the forestry sector and land use” as Minister Bakar posted?

There is a stark difference.

“Halt and reverse forest loss” panders to the popular narrative of “planting trees” to fight climate change. Tree planting exercises may have popular media support but the hard facts and science behind these pop pledges are that they do not fight climate change as claimed.

Take for example:

- Trees are good for a lot of things; carbon offsetting isn’t one of them

- The biggest problem with carbon offsetting is that it doesn’t really work

The independent carbon tracker Carbon Independent sums up the problems well as:

Planting trees will not make a major contribution to tackling the climate crisis. There are many good reasons for planting trees, but sadly, tree planting will not make a significant contribution to the climate crisis.

If the planting of a trillion saplings won’t stop climate change, then surely old forests like those in the lungs of the earth in the Amazonian forests can help buffer its effects?

Maybe not according to the latest report on the Amazon.

As carbon dioxide emissions have surged by 50 percent in 60 years, to nearly 40 billion tonnes worldwide, the Amazon has absorbed a large amount of that pollution—nearly two billion tonnes a year, until recently.

But humans have also spent the past half-century tearing down and burning whole swathes of the Amazon to make way for cattle ranches and farmland.

But its not just cattle ranches and farmland that is changing the landscape. As countries develop, infrastructure like roads have been identified by the FAO as the biggest driver of spatial change.

The environmental impact of roads in African countries invariably point to a necessary and unavoidable consequence of development in less developed countries.

Indonesia has committed to bringing the benefits of development in better healthcare and education to every Indonesian. This is only possible with roads and infrastructure which will have an impact on forests.

In acknowledging the impact of its development on forests, Minister Bakar tweeted that:

“the country’s development agenda must take precedence over the need to combat deforestation, and it was “inappropriate and unfair” to interpret its addition to the pact as a zero-deforestation pledge.”

Seen against the backdrop of failed pledges to protect forests and the new knowledge that forests alone will not be sufficient to stop climate change, the Indonesian policy on Forest and Land Use (FoLU) stands out at COP26 as an example of a practical plan for sustainable development.

The Indonesian FoLU Net Sink 2030 is a superior policy to the simple “halt and reverse forest loss by 2030” as it encompasses all the other elements that are being presented by civil societies at COP26. Key among these elements are the protection of forests by indigenous peoples and the importance of wetlands to mitigating the impacts of climate change, both of which Indonesia has aggressively acted on.

By comparison, the Glasgow Declaration was roundly criticized by Global Witness which stated that:

“While the Glasgow Declaration has an impressive range of signatories from across forest-rich countries, large consumer markets and financial centres, it nevertheless risks being a reiteration of previous failed commitments if it lacks teeth,”

The New York Times was equally critical of the declaration by pointing out that:

More ominous, the often overlooked northern boreal forests grow in soils that hold carbon equal to 190 times the global carbon emissions of last year and are being relentlessly diced and burned. This is accelerating the thawing of permafrost as the planet warms, releasing greenhouse gases in the process.

In the absence of clear plans by other signatories on how their forests and land use will be used to mitigate climate change, the fact that President Jokowi has made the climate ambitions legally binding is what makes Indonesia’s pledge so dynamic. The full report on how Indonesia will bind it by law can read on this link.

Published November 2021 - CSPO Watch

Indonesia has committed to bringing the benefits of development in better healthcare and education to every Indonesian. This is only possible with roads and infrastructure which will have an impact on forests.

In acknowledging the impact of its development on forests, Minister Bakar tweeted that:

“the country’s development agenda must take precedence over the need to combat deforestation, and it was “inappropriate and unfair” to interpret its addition to the pact as a zero-deforestation pledge.”

Seen against the backdrop of failed pledges to protect forests and the new knowledge that forests alone will not be sufficient to stop climate change, the Indonesian policy on Forest and Land Use (FoLU) stands out at COP26 as an example of a practical plan for sustainable development.

The Indonesian FoLU Net Sink 2030 is a superior policy to the simple “halt and reverse forest loss by 2030” as it encompasses all the other elements that are being presented by civil societies at COP26. Key among these elements are the protection of forests by indigenous peoples and the importance of wetlands to mitigating the impacts of climate change, both of which Indonesia has aggressively acted on.

By comparison, the Glasgow Declaration was roundly criticized by Global Witness which stated that:

“While the Glasgow Declaration has an impressive range of signatories from across forest-rich countries, large consumer markets and financial centres, it nevertheless risks being a reiteration of previous failed commitments if it lacks teeth,”

The New York Times was equally critical of the declaration by pointing out that:

More ominous, the often overlooked northern boreal forests grow in soils that hold carbon equal to 190 times the global carbon emissions of last year and are being relentlessly diced and burned. This is accelerating the thawing of permafrost as the planet warms, releasing greenhouse gases in the process.

In the absence of clear plans by other signatories on how their forests and land use will be used to mitigate climate change, the fact that President Jokowi has made the climate ambitions legally binding is what makes Indonesia’s pledge so dynamic. The full report on how Indonesia will bind it by law can read on this link.

Published November 2021 - CSPO Watch